In April 2023, Yorkshire Wildlife Trust, Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust, and Orsted launched Wilder Humber, an ambitious five-year pilot programme aimed at restoring marine habitats and species across the Humber estuary.

Wilder Humber focuses on the connection between habitats, understanding that each different habitat offers an important contribution to broader ecosystems. The programme is implementing a seascape-scale model that combines sand dune, saltmarsh, seagrass, and native oyster restoration efforts to benefit both conservation and biodiversity. By focusing on the restoration of multiple habitats, we hope to see significant benefits to ecosystem services, including increasing biodiversity

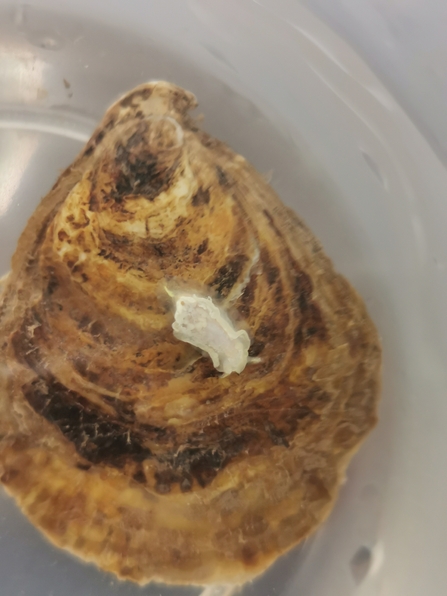

As part of the seascape restoration efforts, Wilder Humber is focused on supporting the restoration of native oysters in the estuary, building upon the successful trial of oyster deployment onto trestles at Spurn Point, which began in 2019.