There can be few animals with quite the cachet of the oyster, yet although now synonymous with luxurious living, oysters were once so abundant that they formed a cheap and easy source of food for even the poorest.

In her "Book of Household Management", Victorian cook Mrs Beeton - the Mary Berry of her day - noted the widespread abundance and ready availability of oysters around Britain's coast...before going on to describe how they should be fried, steamed, coddled and grilled!

Writing a little later in 1883, the Grimsby-based mariner O. T. Olsen published a "Piscatorial Atlas", a compendium of where-to-fish maps which indeed shows extensive oyster banks around our coasts, including along much of the Humber Estuary and down the Lincolnshire Coast.

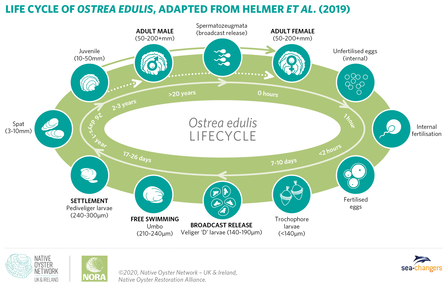

Astonishingly, almost all of these are now gone, and the natural population of our native oyster - the European Flat Oyster, Ostrea edulis, is in a state of collapse. It can be difficult to come by reliable data from the past, but published estimates suggest populations have reduced by as much as 95% since the 1800s. This has largely been as a result of a combination of overfishing, dredging, pollution and disease. Natural stocks are now so low and fragmented that independent recovery from this parlous situation is simply not possible, thus human intervention is needed.

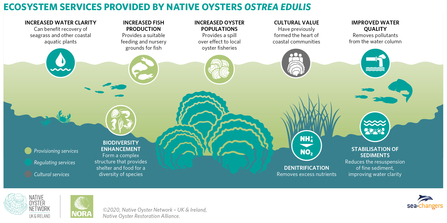

Although not concerned with oyster fisheries for their economic value, conservation groups such as Yorkshire Wildlife Trust (YWT) are actively involved in restoring our native oyster populations. This is because as they grow, oysters build living reefs - not all reefs are made of coral - and thus creates a habitat that can be populated by a myriad of other organisms.

A study published in 2023 showed that historically our oyster reefs were home to an extraordinary 190 marine species representing a huge range of animal and plant types including other molluscs, crustaceans, worms, sponges, fish, seagrasses and marine algae. Even more than that, as the infographic shows, they benefit the environment by filtering and cleaning seawater and by protecting the coast from erosion.